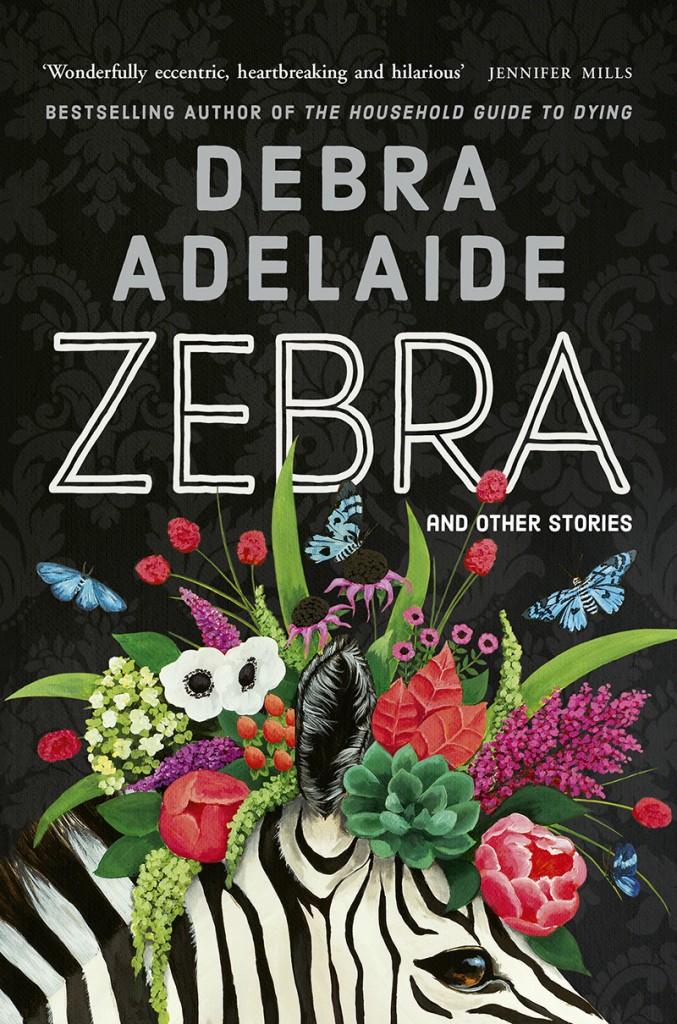

Interview with Debra Adelaide ‘Zebra and other stories’

by Wendy Wicks

Your latest book Zebra and other stories is a novella with an accompanying set of stories organised with a point of view framework. What was the reason for that?

Putting together a collection of short fiction presents a structural challenge for me, and in the case of these stories there is no thematic consistency, nor a prioritised voice, as we often see in authors’ collections. As I was presenting stories from diverse sources, characters, and points of view, I had to think very carefully about the relationship of the stories to each other (could I put a confronting or serious story right next to a comic one? probably not …) and the way the reader might be approaching the book as a whole. Finally I realised that if I focused on voice – first, second and third person – there was some unity.

You have a great time representing the complete knots one gets into trying to please everyone in ‘Festive Food for the Whole Family’. It portrays political correctness gone mad with a wonderful sense of comedy. Is it fact taken to the n-th degree or complete fiction?

It is complete fiction, as for a start I don’t have a large, demanding extended family and don’t host elaborate Christmas dinners. But I do cook, and I do love making a special effort for Christmas. The story was inspired by hearing a radio program one year shortly before Christmas where listeners were invited to call in and relate their worst festive food stories, and one of them was describing how she was preparing for her large family of very fussy eaters. It tries to do two things: capture the anxiety that this festival always imposes on us – especially women – and poke fun at the western middle class fastidiousness regarding food, which is increasing. Food is now somehow feared as well as worshipped.

You clearly are a past resident of Canberra which is the setting for ‘A Fine Day’ and ‘Zebra’. Each are very different stories, the former a tragic tale of dependence and need, the latter a beautiful fantasy. How important is the role of setting to these stories?

I’ve never lived in Canberra and have only made short visits over the years, but like many Australians I feel ambivalent about the place because the place itself is infused with contradictions. It’s the political centre but somehow marginal; it’s progressive but also conservative; it’s sealed off and opaque yet forms the centre of our preoccupations; being a ‘manufactured’ capital it sits uneasily amongst other capital cities; and I also think it represents our overall insecurity about belonging, about taking over Indigenous land, and so on. The first of these stories tries to capture some of the eerie serenity of the city and suburbs where the surface is all so clean and smooth and controlled, but underneath there is darkness, and, as I said, great insecurity. The long story, ‘Zebra’, was partly my attempt to come to terms with the idea of home, what that means to us as individuals and as a nation, and so is set in the emblematic home of the Lodge, which ironically is totally inaccessible (apart from being open one day of the year). But it also looks at much broader notions of home, as in what we are really doing here in this country and why we have not even begun to come to terms with the dispossession of our Indigenous people. To me this is a reconciliation story, though I am not sure other readers would see it that way.

‘Zebra’ is a fantastic tale (in the true meaning of word). It seems to me that there are close parallels with the tenure of Julia Gillard in her role as Prime Minister. Is it at some level a cautionary tale for young women?

Yes, it is a fantasy in every way, and it came from my own fantasy about political leadership which was well before Julia Gillard arrived on the scene. This was during the John Howard years where I despaired of seeing true leadership amongst politicians. Howard had reduced our country to an economy, ignoring everything else that is so valuable – community, cultural and artistic life, the environment – and keeping the conversation only about materiality, about money. He was considered a strong leader because he indeed kept his party under control, but I despise the sort of leadership that refuses to take risks, have long term plans and even visions, and pull us forward to a better future – even if we are unwilling – in the way that great leaders do. My prime minister is essentially everything that Howard et al were not: female, for a start, and lacking any interest in power for power’s sake, with no ego, able to get things done, cut through bureaucracy, improve the country on a local and national scale, idealistic and generous and compassionate. Especially compassionate ‑ where is any compassion amongst political leaders now? The story took a long time to write and wasn’t working for all sorts of reasons, but when Gillard became prime minister (and indeed, the drought broke!) I put it away yet again for what I thought would be for good, because I didn’t want readers to think I had based it on her.

The catalyst in the Prime Minister’s life is a zebra and it is central to the story. Why did you choose a zebra to serve that purpose?

The zebra simply sauntered into the story. But when she did I had to think hard about why I would keep her there, and the answer slowly became clear: as the joke referred to in the story (though not explained) demonstrates, the zebra represents a grappling with identity and with race. Something that is subtle but I hope still apparent to the reader.

I suspect you are a keen gardener from the way plants and flowers are peppered throughout your work – please tell me about peonies.

I have never grown them, and in fact never grow flowers. Peonies will only grow in a cold climate and a small suburban yard in Sydney is not the ideal environment. But I do love peonies, especially their stately yet blowsy appearance, and the great variety of their colours and shapes. Perhaps it’s the fact that they are hard to grow that intrigues me? Or just that in Japan they are referred to – or one variety, anyway, the Paeonia lactiflora – as the prime minister of flowers, which I obviously found irresistible.

Do you write your stories in your head as you are digging in your garden or do you use it to clear the mind?

Both, in fact. Gardening, like walking, is a mind-clearing activity which works to solve problems in stories or open up new ideas. Plus I am a Taurean, so I always feel good with my hands in dirt.

This interview was conducted by a hardworking undergraduate student at Swinburne University.