Review: ‘Fabulous Lives’ by Bindy Pritchard

by Sally Edwards

Fait accompli – the notion that we must accept what is pre-destined for us. We must accept what we cannot change.

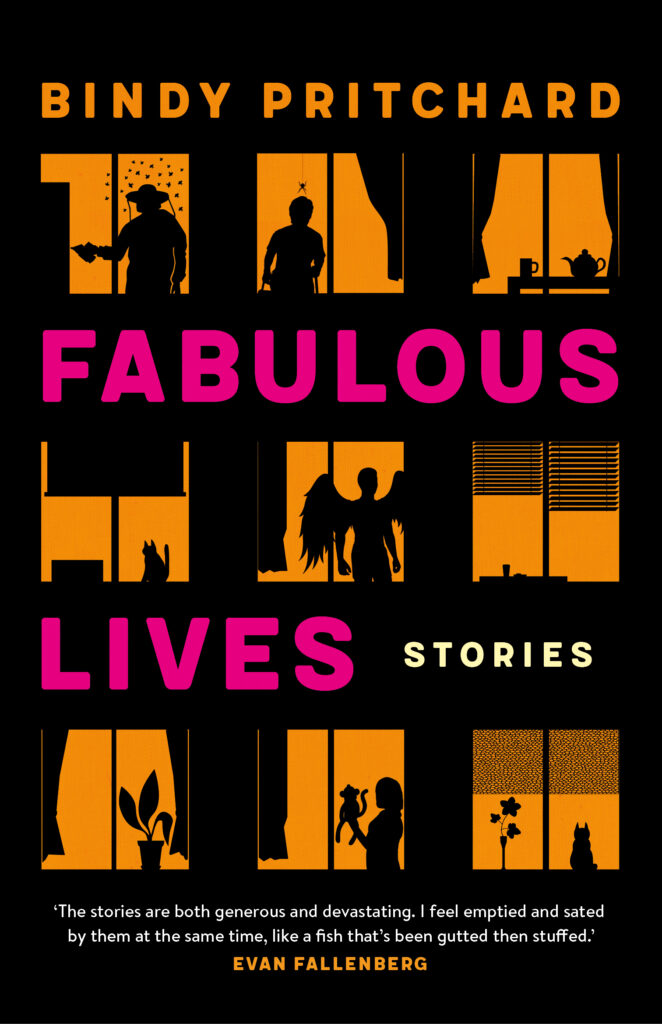

Bindy Pritchard’s debut short story collection, Fabulous Lives, explores the way we, as humans, deal with what life hands us. From cancer, to suicidal mothers, to coming into the possession of a mysteriously large egg. Pritchard’s motley crew – with substance, humour and not without fault – grapple with life’s interruptions spanning from the mundane, to the tragic, to the totally bizarre.

These characters, across sixteen short stories, with their realist approaches teach us to accept fate, to accept our lives as they are, and to accept ourselves, even when they don’t.

‘The Shape of Things’ is the first story in the collection and introduces the reader to the collection’s world where mundane, ordinary domesticity is offset with surreal circumstances and guilty tendencies that go on behind closed doors. A candid reflection of the world we live in and its heaving undertow.

Set against the backdrop of Sydney’s Mardi Gras festival, urgency and energy seethes in this first narrative: ‘you could feel it at cafes; hear it on trains, in hotel lobbies from men dressed in tailored suits – the air was thick with it’ (6).

In the protagonist, Leonie’s, fraction of it all a young man is naked and unconscious on the front lawn of her apartment block, after seemingly falling from the storeys above. A single, middle aged woman, ill with endometriosis and bored with her life, she takes him in. The following pages detail how the trajectory of her life has changed as she shops, cooks and cares for this mysterious and handsome stranger and is spontaneously drawn out of her usual routine and the constraints of her illness.

Through it all, Pritchard carefully writes specific detail that makes familiar domestic routines just as present as the strange circumstances that they stem from:

‘The young man had nowhere to go. It was as simple as that, thought Leonie, as she mashed the avocado into the light sour cream and added the chopped tomato and taco seasoning’ (6).

Balancing the realism with mysticism and magical circumstance is a predominant theme throughout the book and one that drives the readers’ curiosity and affiliation with its characters. Just before he leaves her to join the passing parade, Leonie’s house guest turns into the spiritual figure of Archangel Michael:

‘Leonie gasped at the vision: glistening bare chest, silky white boxers, and rising from his shoulders two magnificent tessellated wings’ (18).

She tries to follow him out onto the street and it is then that the sad fact dawns. This stranger was something new and exciting in her life, a fallen angel, and she gave everything to the fantasy – but, just like that, he is gone, leaving her alone again with the same burders to bear:the memory of her mother, her chronic illness, her isolation. Exciting interruptions like these are only momentary, and then you’re left to live the life that is waiting for you. It is up to you, it is up to Leonie, to create it something to get excited about.

In ‘The Egg’ a middle-class, suburban dad, Bryant, also deals with an almost metaphysical interruption in his life when he comes into the possession of a giant egg. Soon enough, the airport worker becomes enthralled by the mysterious discovery and all of the possibilities it offers to take him and his family out of their mundane, repetitive lives.

Pritchard paints a vivid picture of Bryant’s every day where he plays an almost invisible figure in the lives that pass him, like most of the other protagonists do in this collection, and most of us feel that we are sometimes. He constantly compares his life to others, he longs to be richer, happier, healthier. But his life is so ordinary, so familiar, that the obsession Bryant has over the egg and its promise of a new life, much like Leonie’s houseguest, becomes totally understandable to the reader, even when his rationality wanes.

The egg almost becomes a supernatural force over Bryant, the collection’s signature real versus surreal. It’s hard to believe its power is only about money.

‘Bryant’s sleep was deep but troubled, infused with crazy dreams and an intense heat that spread from his body into the egg – or was it the other way around?’ (99).

Pritchard lends us an insight into Bryant’s childhood, and we learn that he has always lived a plain life in the suburbs and it always seemed to him that his peers had it so much better. She takes us back to 1979, the crash of Skylab, when Bryant would watch the news to see grinning kids and dads holding up new-found bits of debris while his dad remained a silent figure – sitting there with a beer on his belly, shoulders slumped.

Th narrative has many layers and it’s an interesting insight into the modern psyche. Stress, obligation, expectation, these soon lead us to a grass-is-greener mindset where morals can just as soon fly out the window. When it turns out the egg is manmade and fortuneless, in probably the book’s most gruesome scene, Bryant throws the egg to the ground and it shatters into pieces. We’re left wondering where Bryant’s ruthless dreams for a better life will go now. Will they be shoved back into that compartment of his brain with Skylab and his dad’s beer belly, or will he accept the goodness that exists already, or, will he keep pushing for something better with dignity?

More than any perhaps, the title story, Fabulous Lives, plays with this epidemic of envy. Set in New York, an Australian aged-care worker, Edith, is there to meet up with her best friend from acting school, Ricky.

Ricky keeps cancelling on her and the themes of geographical and personal displacement, high school anecdotes, and Edith’s current state: alone in New York, teach us that this is a friendship very much based on the past.

Their friendship is a history rather than anything significant now, in fact they haven’t seen each other in years. Pritchard describes their friendship intimately, and its one that we can all relate to. She shows the way in which friendship can diminish, especially in the modern age with the smoke and mirrors of social media. But as Pritchard allows us to see into their friendship through carefully structured past versus present anecdotes, we start to understand why Edith was willing to cross the world to meet up with Ricky.

To Edith, her life back home is mundane and nothing to be proud of, but when the truth unravels about Ricky, that his life is not as it seems, she starts to see the fabulousness in her own. She sees references to her retirement home job and the bingo games she runs through numbers on the street: legs eleven, two fat ladies, turn the screw, and her fondness for her life and the familiar emerges from her truest self.

Like in ‘The Egg’, we see in ‘Fabulous Lives’ that comparison is the mark of modern demise. While her characters chase after other people’s lives or lie about their own, Pritchard’s motif of fait accompli comes through as a reassuring message – warming and a magnet for gushing inner-gratitude.

The emerging theme of illness plays an important role in this collection. From the second story ‘Dying’ up until ‘Last Days in Darwin’, illness, as a sadly common interruption in life, highlights how althoughit affects almost all of us every day, it still has a way of making us feel so alone.

In ‘Arrow’, mental illness has come between a mother and son. Though they live in the same house, high school career guidance counsellor Fran and her twenty-something son Damien do not speak. He doesn’t leave his room when she’s there but there are remnants of him in the slop at the bottom of the fridge and empty packets of food.

‘She wonders if Damien is still wearing that same tartan blanket poncho… Or whether his skin is still as pale as the cabbage moths that flutter like paper over the tomato bushes’ (136).

Her only relationship with her son is through memories, for which Dulux paint colours become a symbol. When Damien was young, they used to rename the paint colours together – an inside joke. Fran wonders what has gone wrong that they have both ended up like this, their relationship diminished, him locked away in his room never talking to her.

‘But then he had chosen black. The blackest of black. Painted over each and every hesitant blue stripe until the bleak oily walls absorbed all colour and life’ (143).

It’s clear Damien is depressed but Fran blames herself for his reclusive, damaged nature and becomes obsessed with what could have been for the both of them. Standing in the Bunnings paint aisle, surrounded by swatches like those on the career bullseye chart at the Department of Education office and all of its ‘colourful rings of possibility’, Fran dreams of all life’s possibilities for her and Damien. She wonders about the Bunning’s employee and whether Damien, too, could work in a place like this. She wonders if being with a man would have made a difference in Damien’s life. Or is he the way he is simply because of her and their biological connection?

‘Who can really know someone unless you prise open their skull cage and step inside? A baby would know though, wouldn’t they? Absorbing more than just nutrients through the womb wall: the mother’s thought patterns, silent conversations, the nervous beats of the hand and the heart’ (139).

Fran’s defence of her son is endearing at first. She longs for him to be how he used to be and not the ‘resident ghost’ any longer. But at work, Fran’s behaviour almost reflects that of Damien’s. She segregates herself from her co-workers in order to avoid their judgment and criticism of him and ‘the arc of her day becomes smaller, too, like Damien’s’ (137).

Her own anxiety begins to throb. She doesn’t care about losing her job, for why would she want to help guide students on their future when she couldn’t even help her son? ‘No one ever grows up wanting to be a career guidance counsellor, or the mother of a son who cannot step one foot outside the front door’ (145).

The heartbreak of losing her relationship with Damien to the grips of mental illness comes to a crescendo on the final page when, unaware that his mother is up, Damien goes outside – something Fran didn’t think he ever did. Through the glass door, she mistakes her own reflection for his – ‘The gloss of youth shriveled away – wispy, thinning hair and dead eyes’ (147).

Her son’s illness is her own, and hers is his. But in this breath, if she were to get better, be happier, would he? There’s no certainty in the answer as there is none in life and that’s a hurdle that all of Pritchard’s characters have to face.

The stories and characters in this collection are exceedingly diverse but their shared themes and Pritchard’s wise and endearing voice binds them. Pritchard really knows her characters – their ins and outs, fears and fantasies and, in these pages, the reader gets to really know them too. But there remain leftovers from the feast, leftovers for the reader’s mind to digest with imagination and guesswork.

When all the pages are turned, we as readers are left with a new outlook on humanity and all the different kinds of fabulous lives that are led behind closed doors. We’re left with at least sixteen more people we know deeply, however fictional they may be, and the world as we know it feels a lot less lonely. Resoundingly and above all, this book is about appreciating your own fabulous life, it is the only one you’ve got.

This review was written by a hardworking undergraduate student at Swinburne University.