Review: ‘Australian Short Stories’ edited by Bruce Pascoe & Lyn Harwood

by Suzanne Masri

Australian Short Stories sheds a light on the human condition within a conflicted, magnificent landscape that is distinctly ours. The collection explores the sphere of each character’s world to appreciate a collective consciousness of belonging, place, and survival.

Australian Short Stories is a multi-author collection which encompasses philosophies of culture, family memories, love, and loss on the canvas of our striking Australian landscape. Edited and compiled by Bruce Pascoe and Lyn Harwood, the smooth-covered book is the latest collection published since the year 2000. It comprises sixteen stories incorporating established and emerging writers including Julia Prendergast, Claire Aman, Archie Weller and Daniel Browning amongst others.

In his non-fiction piece ‘Water Country’, Daniel Browning reflects on place and its embodiment of state of mind, spirit and substance. The story is enriched with family history dating back to three generations ago when rough seas had damaged the Browning family’s esteemed three ships: Mystery, Swan and Hero. The ships’ names are placed in separate paragraphs to convey the loss of livelihood the family experienced from each of their cherished ships.

Browning addresses the reader in the second person perspective with a conversational tone that establishes a connection with the reader. A scattering of words in Bundjalung construct the meaning of home and the headland being like an echidna, a ‘series of basalt columns spat from the volcano they call Mount Warning’ (7). The story is infused with a composed lyricism and the rich description of place encourages the reader to engage with the setting in a sensory way: ‘I know I’m at home when I hear that particular timbre of the ocean buffeting the shore’. A new paragraph invites the next lyric ‘A long, thunderous echoey drone¾sometimes, a low, barely audible whisper’ (7). His use of simile is once again outstanding as he talks of almost drowning in an underwater cave when he was eight-year-old: ‘Then the cave expelled me, like it was clearing its throat. I was safe’ (9).

The narrative is structured in flashbacks and memories, such as the one he remembers of his great-grandmother: ‘It’s there on the edge of the water that I can see my great-grandmother May; she’s patiently tending a handline’ (9). Her character, qualities and routines are revealed through repetitive paragraphs of ‘I remember’ (10) reflecting the lovable woman she was and the comfort she had given her family.

In ‘Slow Time’, Julia Prendergast’s signature style reveals itself in her rich, explorative rendering of how a newly-single mother, Beth, deals with the aftermath of her husband Ross’s cheating and his departure from the family home.

Ross’s absence prompts Beth to find a renewed stability for her two children, Luke and Rachel. All three members of the family struggle as they overcome feelings of betrayal, abandonment and resentment. Beth and her son, Luke, are at heads with each other, and Beth feels she is being blamed for Ross’s actions. Unappreciative and disrespectful towards Beth, Luke turns to drugs and spends his nights sitting in his father’s abandoned car, much to the dismay of Eva, the meddling neighbour.

Beth’s becomes detached from her world and this is highlighted as she looks past her nagging neighbour ‘as if gazing out at the weather’ (14). Beth’s anger is reflected from the very beginning of the story in the detail of having thrown her husband’s possessions in the back of the car, one of them a smashed teapot in the windscreen, ‘only the curved spout was left intact, milky white and useless, like Ross’s measly penis’ (14).

The dialogue is witty and engaging and the reader resonates with the family’s tense interactions with one other. Beth’s varied emotional states reflect the turmoil her character is experiencing and the reader is handed glimpses of Beth’s racing, evaluative thoughts within the metaphorical use of focus and perception in the narrative.

An ethereal shift occurs during Beth and Luke’s reconnection in the car. Beth’s devastation is tangible when she eats her neighbour’s casserole ‘…chewing slowly, then a piece of chicken. Glossy juice dribbles down her chin’ (21) then a suggestion of release or a resolution when ‘she smiles at Luke, but she’s crying noisily too¾tears like painless blood’ (22). She has felt the pain; the tears do their necessary human job of shedding.

The iconography of the smashed teapot returns when Beth looks back at the coloured shards reflecting through the broken back windscreen: ‘As the streetlight hits the fine china, the light refracts against the purple and white so it looks like stars, scattered across the rear deck’ (22) and this suggests the concepts of optimism and growth.

‘Slow Time’ addresses the many battles of Australian women and the inner strength they are unaware of having. Prendergast’s intertextuality is unmistakable and her expertise in the psychological depth of characters reinforces the narrative further.

Similarly, Prendergast’s ‘Ghost Moth’ depicts true-to-life characters communicating in colloquial dialogue while the narrative weaves metaphor and stream of consciousness together. The story addresses child abuse and motherly abandonment: farmer and single father Chris and his daughter, Rachel,d struggle to accept Rachael’s mother Edwina’s departure years ago after having abused and left Rachel ‘squealing, gurgling blood like a baby lamb’ (57).

After some time, Rachel had returned to the farm with her baby son, Edwin, in her arms and observes her father birth the ewes. Chris’s anger is revealed in his furious vents about the foxes who rip soft parts making the job, in helping the ewes give birth, more difficult. Likewise, his anger is directed, in metaphor, at Edwina: the fox may be read as a symbol of the mother’s abuse.

Rachel’s abandonment as a child is reflected through Edwina’s old abandoned spinning wheel: ‘The bobbin is half spun. The wheel is as still as concrete. It marks the mother’s leaving solemnly. The wheel is called a maiden; the maiden wheel has hooks on it, sharp as a fox’s teeth, sharp as a mother in a half- spun love story’ (54). The reader may understand the spinning wheel and the action of weaving is an object of a mother’s love, and its non-use symbolises the lack of it. The irony is not lost; Edwina is a weaver by name, as no love for Rachael had ever been ‘woven’ at all.

Rachel’s need to return to the farm could be attributed to suffering post-natal depression, thus needing to feel closer to her father: ‘She packed hurriedly, acutely aware that she needed her father—knowing it boldly, with the same blind certainty that she suddenly understood mis-mothering’ (57-58). Perhaps Rachel recognises her mother’s parting may have been ‘unintentional’ and a loss of focus in motherhood is somewhat natural.

Scenes flit back and forth in past and present hinting at what happened before. Prendergast’s sensory detail is evident when Rachel contemplates, perhaps with a sense of hopelessness, the grey threads of her mother’s leftover fleece in contrast to the ‘grey moth carcasses, littering the veranda like dirt-flecked yarn’ (54) and the grey rockscape of Stone-Dwellers country.

Claire Aman’s ‘Japanese’ is an analysis of the human quest to find the original and distinctive in a vast landscape. An adventurer’s solitary existence is revivified when she comes across a Japanese motorcyclist she calls ‘Mr Suzuki’ in South Australian country.

We travel with the narrator¾ newly divorced librarian and perhaps on an adventure of self-discovery¾ through Yunta, Port Augusta, Uluru and Carpentaria Highway and she interprets the encounters she has of the Japanese man as if they were an ink wash painting. The brush strokes become stronger or lighter depending on the feelings the narrator experiences during the encounters.

In her first encounter of Mr Suzuki, the brush strokes are bold as the first sight of him attracts the narrator’s interest and admiration. His image stands out in the scene as she remembers him, captured with the background left blank; hinting at her solitude where ‘even the slenderest thing can seem like something’ (46). Later, curiosity propels the narrator to stop watching from behind her campervan window and the two have a brief conversation.

Later, she learns that his existence is just as solitary as hers, painting the sad story with a ‘swift’ and ‘delicate’ brushstroke (49). The story is narrated in first person; yet, introspection is scarce and this somewhat distant voice of the narrator may be seen to reflect a reserved character. Nonetheless, the story refers to a sense of place similar to Browning’s metaphysical one. Optimism and hope are emanated through sensory depiction of landscape in which magic is discovered and lived.

Maureen O’Keefe’s ‘The Laucke Flourbag’ is non-fiction filled with nostalgic memories of her resourceful, hardworking mother during simple, happier times. Maureen’s mother had been a dressmaker who sewed clothes and bags for bush tucker with the cotton Laucke flourbags before they ended in the early 80s. The flourbag is a symbol of love, home, and survival.

Through the flourbag, O’Keefe feels more connected to her mother who seems to have been the reserved kind and expressed love with actions more than words: ‘She didn’t tell me what was in her heart. She just made things’ (75). Being a horse rider and buggy owner for transporting older hunters, the mother represents other admirable Aboriginal women who did multiple jobs and were resilient for their family. The symbol of the Laucke flourbag represents a sense of identity that gives value to this story; the narrative’s authenticity is further enhanced by the narrator’s natural conversational tone and the use of idiosyncratic spoken dialogue.

In Kim Scott’s ‘Bees’ the narrator speaks to the reader in a similar colloquial tone of voice. He is a white man whose old Aboriginal neighbour ‘old girl’ comes to him for help in removing bees swarming in her chimney. Scott gives the reader intense visual sensory detail: ‘But then I caught the tears, saw her hands shaking, the lines of her face asking for help’ and ‘the hand at the end of his arm was like something separate, like an animal all of itself’ (25, 30).

Sharp sentences quicken the narrative’s pace and the dialogue either flows in quotations or without, such as ‘I been on the phone, ringing, ringing. Telling her all the time, I’ll sort it. Relax’ (26). Tension builds as the narrator’s frustration intensifies into anger at the bee killer, absorbing the reader’s attention till the end of the story.

Whereas Maureen O’Keefe portrays the homely and resourceful mother, ‘old girl’ is depicted as someone whose past involved bad choices and an awareness of mixing with the wrong people: ‘Dancing with the sailors, too, but she wasn’t dancing, she was just treading water. So nervous all the time’ (25). The reader is also given the idea of an insecure woman who yearned for approval and security by ‘sucking up’ (25) to those who were white or authority figures. Therefore, the narrator feels perplexed at her fear of the unknown: ‘Bees, they my totem. Native bees, anyways. But, these bees now they’re not native, are they, are they?’ (24). Her fear also suggests concern for her son Arron who battles violence and drug issues.

Archie Weller’s ‘Shadow on the Wall’ examines the truism that loneliness, loss and pain do not differentiate between race. The setting is based in an outback prison in which there are three inmates: an Aboriginal tattooed thief called Spider who was stolen from his mother as a child and molested by his white foster father, an Aboriginal dreamer called Gary who envisions himself becoming a famous singer and finding his long-lost brother, and Donny who is a white bank robber betrayed by his ex-girlfriend and the brother, Jimbo, he still thinks of.

The story regularly refers to a metaphorical concept of ‘shadow’, perhaps symbolising elements of the characters’ lingering pain from each of their pasts, with nothing left but for each to fend for himself. The narrative is structured through Donny’s silent, cynical observations of the two Aboriginal youth struggling to get along, and backstory of each character is interwoven between dialogue. Characters’ speech is formed with original colloquial slang and Aboriginal language contributes to the authenticity of the characters. Donny’s somewhat racist thoughts trigger a shock-factor with words such as ‘abos’ (83) and ‘annoying little black flies buzzing around his head’ (86); however, this is an honest reflection of social and racial tensions which prevail to this day.

Weller’s sensory description is not too different from Kim Scott’s; his methods of capturing thoughts, objects or scenes are striking, such as Donny’s contemplation of living his remaining older years ‘in the tatters of the dreams he held like fine silk once not so long ago’ (86).

Weller does an impressive job at entwining different backgrounds to unite as one parallel concept for all three men. It contributes to a commonality for all three characters with a surprising twist which propels the reader to return to the beginning to the story and re-read the dialogue. Despite Donny’s negative observations, his character comes through in the end and enhances the story’s outstanding representation of brotherhood.

Gillian Mears’ ‘Heart Stones’ is a story representative of the radical effects one’s childhood could have on one’s future. It adopts the first-person perspective of a little boy called Davey who loves but feels resentful of his mother’s inattentive behaviour. His mother gives sexual services to a stranger called Mr Metherill at home because of her dire financial situation.

The story flits between past and present effortlessly and Mears’ portrayal of Davey’s curiosity and child-like wonder is effective in creating credibility. Davey is unaware of his mother’s depression and he senses her pulling away, measuring her unhappiness ‘an inch or two deeper’ (31) while he learns to measure everything in inches with his ruler. Mears portrays his child-like excitement effectively when Davey shows his mother a light making the shape of a heart over her dress by a high front window; the distance between him and his mother returning when the light ‘lost form, danced into another shape altogether’ (32).

Sometime later, the vision of seeing his mother in the midst of a sexual transaction with Mr Metherill has a profound effect on Davey’s future and he suffers chronic detachment in his relationships. He refuses to combine sex and love, and is intent on repeating or rather watching the girl he loves, Nerida, imitate the scenes he witnessed of his mother: ‘If his memory of his mother has become a piece of poetry, he believes only the crudest acts might help him remember the missing lines’ (36). All the while, he feels guilty for his mother’s suicide, forever holding onto a heart stone he never had the chance to give on her birthday.

The reader may find it difficult to adjust to scenes that may feel too far-reaching or occur too soon in the narrative; however, Mears was successful in her exploration of psychoanalytic practices and in addressing harsh experiences of the past.

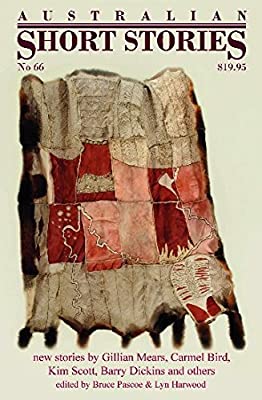

Australian Short Stories is a delightful collection that embraces a central premise of survival within authorial visual, emotive and phycological concepts essential to storytelling. Authors from unique walks of life have united to share their stories of life journeys, values and what it is to be Australian. Themes which would otherwise be too daunting or confronting were expertly expressed with rawness, courage and honesty. The book also features wonderful, introspective illustrations and the artistic creation of the Grandmother Cloak on the cover.

This review was written by a hardworking undergraduate student at Swinburne University.